Language within Art and Photography: Exploring the Vehicle of Communication Between the Artist and the Viewer

Figure List

Figure 1. Magritte, R. (1929). This Is Not a Pipe.

Figure 2. Bochner, M. (1969). Language Is Not Transparent.

Figure 3. Anastasi, W. (1962). Word Drawing Over Short Hand Practice Page.

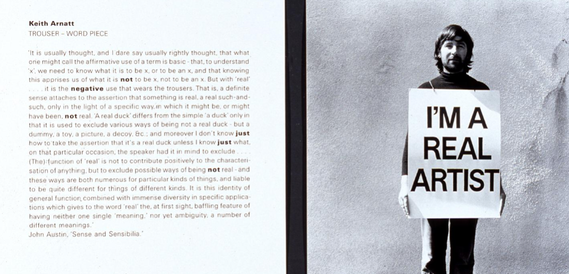

Figure 4. Arnatt, K. (1972). Trouser- Word Piece.

Language is a central development in human condition where, by means of a shared agreement, we can communicate freely and effectively. Language unites a community and strengthens bonds within one another as a society. Language lets us influence people’s behaviours in greater detail. The breakdown of the meaning of language has continued to evolve so there is difficulty drawing a definite explanation though it has been simply defined by W.L. Barber in their book The Story of Language as “a signalling system which operates with symbolic vocal sounds, and which is used by some group of people for the purposes of communication and social operation” (Barber, 1972, p.21). To understand and interpret each other to succeed in everyday communication, we have signs and systems under the term Semiotics developed by Swiss linguist Ferdinand deSaussure. Semiotics can be separated into two parts, the ‘Signifier’ and the ‘Signified’. Where there is an object in the world with a decided term or name, there must be a certain recognition and mutual understanding for it to function with that degree of said recognition. For something to be named, it must be equally agreed on by whom is viewing the object.

Thinking about semiotics, we naturally lead to Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein tests the limits of language by proposing that if the signs and systems were not agreed upon, we would struggle to follow any cohesive, verbal communication as there would be no settlement each sign’s meaning. Relaying this back into the context of art, works began centring on the condition of language and seminal investigation as well as the use of text alone for artistic purposes. With the founding ideas and theories, language philosophers such asJacques Derrida and Roland Barthes along with rising artists such as Bruce Nauman were influenced by Wittgenstein and used language as a forefront of artistic and philosophical concern.

When discussing both art and photography, language is a crucial element in the communication between the artist producing the work and the viewer interacting with the work. For the artwork to succeed in communicating to a larger audience than the artist themselves, the work must utilize language in either the written word or by generating a visual language. The incorporation of the written word and the image alone hold an inextricable link to language but both adhere to opposing forms.

by Lucy Shortman

A beginning example is from the 1920s Surrealist movement, which commonly used text to question rational logic and experiment with its possibilities. In Surrealist artist, René Magritte's 1928 work ‘The Treachery of Images’ also known as ‘This is Not a Pipe” (fig.1), there is an illustration of a pipe with the statement “Ceci n’est pas une pipe”. The work aims to underline the discourse and contradiction when language interferes with the pictorial image bringing forward the underlying questions of representation.

French philosopher Michel Foucault’s 1968 analysis of the painting raises questions concerning authenticity and the object as drawing being used as a means of representation. Foucault discusses the difficulties regarding the work stating:

There are two pipes. Or rather must we not say, two drawings of the same pipe? Or yet a pipe and the drawing of that pipe, or yet again two drawings each representing a different pipe? Or two drawings, one representing a pipe and the other not, or two more drawings yet, of which neither the one nor the other are or represent pipes?

(Focault, 1968, p.16)

Foucault discusses how Magritte pins down the complexities of both language and meaning, word and sentence. By using the word ‘this’ suggests all aspects of the work. Is Magritte talking about the drawing, the text, the canvas or the word itself? The word pipe does not constitute the embodiment of a pipe but rather its linguistic quality whereas the picture of the pipe is a mere representation of the thing itself. The work, therefore, highlights the relationship between form and content. In this instance, the form is the sentence and painting, the content is the meaning of the work. This content changes the context of the work in the way Magritte assembles the piece together. In the context of the communication between the artist and the viewer, the viewer can understand the image and text by signifying its resemblance to that of the pipe’s physical existence. This relates back to Saussure’s theory on the ‘Signifier’ and the ‘Signified’ as the thing is recognised and addressed by means of signification. Magritte illustrates how language is used as a vehicle to reveal a concept or idea from artist to viewer as Magritte speaks directly to the audience, forcing them to question the significance of the sentence and its context in relation to the picture. This was one of the various methods artists used language to communicate with the viewer while starting to cut through the age of conventional approaches in art.

Art and language during the Conceptual art movement

The rise of language in art led to changing attitudes within the work’s potential and the birth of new contemporary methods. Language was and is still used to notate and communicate for everyday understanding. An exemplar of this is the experimental musical composition of the 1950s. The scores and recordings aided the reader to recognise the music if they were not trained or skilful enough to listen and understand without prompt. There were also alternative versions of the same composition so the piece was never performed the same. Influenced by this, language, specifically text, was integrated into art so the observer may be able to comprehend elements of the work by its established structure which they may not have understood beforehand without the text. The duality of art and language was common during the conceptual art movement with central figures such as Sol LeWitt, Victor Burgin and Lawrence Weiner all seeking new techniques of making work.

Conceptual art originated in the early 1960s attaining its full recognition as a movement towards the later years of the decade. Form and visual art were crucial foundations of the conceptualist’s works and the procedure of language was frequent. The movement derived from investigations of philosophers to the artist’s interpretation of the idea. In some instances, language was denoted of its meaning and in its place, was its relevance for visual quality. The “openness of the situation” (Alberro, 1996, p.80) and the artist’s approach conveyed a different dimension to the work. Language was innovative and revolutionary while also necessary in certain contexts. It delivered a conclusive element to the work where a concept could be written, therefore, meaning was accessible in the work by the language of which was presented. The vast opportunities text gave to an artist is spoken of in Yve Lomax’s book Writing the Image where she states the purpose of text in art as “The desire as a visual artist, to find out what writing can do, what it can develop and envelop” (Lomax, 1999,p.23). By incorporating language into the work, the artist has an opportunity to influence the viewer directly.

Concentrating on the use of language in art and its relationship with the viewer, it is important to examine how influential this was for the success of the conceptual artist’s work. As there were little boundaries for language when integrated into the movement, the medium gained its own respect and a fresh purpose. In her book, Words toBe Looked At, Lisa Kotz observes these methods stating that "Preparatory materials may be as interesting or even more so than the produced work" (Kotz, 1999, p.48) underlining the common themes of conceptual art where language acted as a discipline and routine not only as a method of artistic assembly.Notational methods expanded towards sculpture, performance and photography in the context of written language. This relates back to an earlier point about musical compositions and its association to language and art. Where there are constraints within a tape recording, for example, there are constraints for an artist and their proposed structure for producing work. To elaborate, the tape that records the music limits the musician to a set amount of time to compose however, the music which they compose is solely open and up to chance. The experimental nature of this method directly links with conceptual art and its idea of breaking through the boundaries of high-modernist paradigms. Conceptual artists would set themselves pre-determined limitations and structures in the creation of their work, however, the outcome was entirely open for interpretation.

Conceptualism embodied“art about the cultural act of definition” (Osborne, 2002, p.14) where possibilities began to be pushed where further mediums were introduced to examine the relationship art had with language. Language created new-found, visionary qualities and shaped opportunities for artists experimenting with form. The gestural, methodical and theatrical attributes of language allowed room for artists such as Mel Bochner to react with the spectator. Methods such as textual recordings, instructions and limitations of the artist were prominent which brought the viewer closer to the artist and allowed them to see inside the creator’s mind and comprehend the hidden agendas of the work. Looking at prominent conceptual works at the time, the communication between the artist and viewer was a significant element to its success with its intention to alter a way of thinking and speak to the viewer in a way not directly visual to the eye. Artists used text as a chance to cloud content with meaning and confuse the viewer by using the power of context to their advantage.

In Mel Bochner’s 1969 work ‘Language is not Transparent’ (fig. 2) where we, as the viewer, are invited to recognise language in two forms. Firstly, as an objective to recognise it for what we see in its literal form. Secondly, as subjective for what Bochner may be implying otherwise. This is a critical duality to recognise when considering the communication between artist and viewer. As the viewer of the work, we allow ourselves to select the language in which we comprehend and process Bochner’s idea. Studying Bochner’s work in the gallery space, its function could be considered useless without the act of the visitor. For the work to succeed in communication, there is a need for an audience and furthermore, a direct relationship between the artist to the viewer. Bochner’s concern with form is relevant here and with that of the works during the conceptual art movement.

Art and text during the Conceptual Art Movement

Continuing with conceptual art, we are going to focus directly on text and its involvement in conveying language in art. The use of text as a medium was becoming equal to visual art as words could now speak what painting could not. Anti-aesthetic qualities, influenced by early conceptual artist Marcel Duchamp, were reinvented into a new language where the form was indispensable. Text was an uninterrupted route for the artist to communicate with their audience whereas the viewer could use the text to recognise the context or intention of the artist. In contrast, text would furthermore be used as a juxtaposition whereby the artist could assert power over the viewer, by deceiving truth or reality. Victor Burgin, a key writer and artist of the movement, illustrates the possibilities of text as such:

Outside discourse, words acquire relations of a different kind. Those that have something in common are associated in memory, resulting in groups marked by diverse relations

(Burgin, 1982, p.44)

The viewer can appreciate the work with text that is accustomed to them. Whether they understand the artist’s intention is irrelevant at first sight as the audience’s instinctual reaction is to put themselves within the work and relate to it. Both elements influence the relationship between the artist and the viewer and what is communicated whether intentional or unintentional.

An important example of text to address takes place in the work of American artist William Anastasi. The prominent artist in both conceptual and minimal art worked towards experimenting with the autonomy function of art objects. Here is one of two works of Anastasi’s 1962 piece ‘WordDrawing Over Short Hand Practice Page’ (fig. 3). The text-based art addresses the juxtaposition of language and the interruption this may have with the viewer’s understanding of its context. The work is spoken of in N. Elizabeth Schlatter’s 2013 essay Art=Text=Art:Works by Contemporary Artists where it is said that the works “notonly exhibit semiotic connotations, they also suggest the diminishing utility of as a means of notation and communication.” (Schlatter, 2011, p.3).

Where the short-hand writing overlays the written words, it is discovered that they are not connected and instead have two singular meanings irrelevant to each other. By juxtaposing the two texts together, the context of the work is changed making language visual experimentation rather than that of a functional, communicating system. The gaps between the squiggles of short handwriting create tension in the language of the work frustrating the viewer into an endless search into the connection between both forms of text. The language, therefore, becomes a painting or drawing rather than writing.

When considering both the artist and the viewer, text was used for different purposes aside from juxtaposition. With broader and advancing disciplines such as sculpture, installation and photography, artists from this movement experimented with how language could be pushed as an aid in their work to enforce viewers to listen to issues they sought to raise. Leading conceptual artist Lawrence Weiner is a key artist to mention when examining the use of text within art.Weiner works with typographic texts in the form of sculpture and looks to recognise art as an absence in the form of language. Regarding his use of language, he expresses how he can combine text with material hence why his work, at times, presents itself out of the gallery space. His work aims to engage the audience with the use of text and performative instruction is clear and available so that it can be understood by a mass audience. The interest in the constant complexity of the thing and its representation is inherent in his practice. Bearing in mind the context of the communication between the artist and the viewer, this is a vital factor regarding his practice. In an interview with Nika Knight, Weiner speaks of his work’s relationship with the respondent: “Once you know about a work of mine you own it. There's no way I can climb inside somebody's head and remove it.” (Weiner, 2007, np) Here, he addresses the language that feeds its way into the viewer’s conscious and further, subconscious. It is constantly present and the text displayed becomes the art which begs the question whether it is language in art or art itself. The work is no longer a physical form but that which is transmitted through the mass audience. Relaying back to Words to Be Looked At, Kotz explains further that “Weiner’s explicit activation of the receiver is modelled on the implicitly performative positioning of the viewer/reader/listener” (Kotz, 1999, p.98). The audience of the work is crucial to its success and is applicable to the viewer’s everyday existence. This highlighted theme of language running through conceptualism helped to shape the future of art and the prospects of how a piece of work could closely influence a viewer, further than the visual eye only.

Photography after Conceptual art

Where we have explored the use of text within art, it is essential to highlight an additional but still relevant pairing during the 1960s, text and photography. Conceptual art was significant in its birth and led to a new liberation of imagery and its potential. A question that is asked at this point is if the medium didn’t matter in conceptual art, how do we introduce photography and language into its own medium? The photographic vehicle was ever-changing during this period and was rising with broader disciplines and techniques of photographing the world outside of the conventional. This was a leading expansion on how the world could be represented accurately without the sole use of writing. Having said this, photography was developing a new breed of photographers who were breaking through the history of the image only being used as record and document.

Considering the success of autonomy and deadpan photography in the works of Ed Ruscha’s Twentysix Gasoline Stations, here lies the status of text supporting image. The effective combination of text and image is present in Ruscha’s book and offered him a chance to present context to his photographs and assert a power on the viewer's reading of the work. Text and image “generate two complementary codes running on parallel tracks, each holding the key to deciphering the other” (Gilman, 1980, p.61) and the unity serves immediate language to the viewer, supporting the framework that Ruscha created when photographing the gasoline stations. The significance of combining text and image together is spoken of in W. J. T Mitchell’s Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology where the importance of words is addressed with Mitchell stating that “Words, when well chosen, have so great force in them that a description often gives us more lively ideas than the sight of the thing themselves.” (Mitchell, 1986, p.23). This is established in Ruscha’s book due to its arresting title, the words gain the attention of the audience and we, as a viewer, are drawn further into the photographs where we naturally make associations between each image. Language in the form of the written word has the power to aid the viewer in speaking what the image is signifying. It similarly allows different mediums of art such as photography and literature to fuse together.

Where“the meaning of any photographic message is necessarily context-determined”(Sekula, 1982, p.85), images need to be contextualised dependant on the scenario in which the photograph is taken. For example, if the photographs are for documentary purposes or used as evidence, there requires a grounding of context to guarantee there is no misrepresentation. This leads to captions of images, paragraphs carrying a narrative to the images or perhaps, headlines or quotes to inform the audience. In Victor Burgin’s’ Thinking Photography he states that “the putatively autonomous ‘language of photography’ is never free from the determinations of language itself” (Burgin, 1982, p.143-44). Again, Ruscha’s Twentysix Gasoline Stations highlights this and permits the viewer to recognise what the imagery may not conclude itself, through a language that they can read and understand as a form of signification. The title of Ruscha’s work is fundamental in its success as it leads the viewer to certain connotations and possibilities the photographs may evoke. N. Elizabeth Schlatter touches on this idea of the viewer’s interpretation by stating “Due to their evolving relationship to text, contemporary art viewers bring an expanded range of interpretation to their “reading” of artwork that incorporates text.”(Schlatter, 2011, p.3). The use of text was beginning to be frequently used whereby the audience could each look at the work individually from an inimitable perspective appropriate to them and how they feel when viewing the artwork.

Discussing the combination of image and text, it is vital to underline its occasional association with theoretical practice. As mentioned previously, artists were often influenced by practitioners, precisely those that investigated language and semiotics. In some cases, both would fuse where the theorist became part of the piece.

To give an example, we look at ‘Trouser-Word Piece’ (fig. 4) a 1972 work created by British artist Keith Arnatt. The work features an image of Arnatt with a plaque around his neck that reads ‘I’MA REAL ARTIST’. To accompany this is a collection of text quotes from philosopher John Austin that talks about the subtleties of language. Arnatt is spoken of in Martin Herbert’s Art Monthly article in 2008 which sees Herbert stating that “contemporary art offered few fresh avenues for exploration, and his response was a reflexive turn: an approach predicated on the problem of being an artist” (Herbert, 2008, np) Arnatt claiming himself to be ‘a real artist’ begins to raise questions of what does it mean to be an artist and what accreditation do you need to prove yourself to be an artist. This work emphasises the complexity of language and its power of misleading its receiver.

The use of the word ‘real’ is important at the time of this work’s creation. During the early 1970s, many artists were experimenting with photography and the idea of the real, whether that be using real materials or real spaces. Arnatt uses his easy-going ideal of the artist to play on this title and addresses that it is irrelevant if you are an artist or not an artist. With the use of language, you have the authority of an artist by means of signification. Language can assert power and leads viewers to be manipulated into what they believe or don’t believe. Through the trialling of text and image at this time, the experimental photography of the 1970s excelled, reviving a new spirit of photographic possibility. The two methods of language, one written and one visual, led to a complementing unity, both working together to aid the other in either communicating the artwork’s message or utilizing the dualistic processes of language.

The language of a photographic image

Though image and text was a useful tool for an artist, there was and is an importance for images to be exhibited without text. Language is apparent in the photograph alone albeit presented in multiple ways to convey a certain message whether clear or unclear. Photographs opened doors to interpretations and led viewers to make their own assumptions for the meaning of the work. Street photographerAlex Webb addresses the process and subsequent feeling of taking a photograph where he expresses “I sense, almost smell, the possibility of a photograph” (Webb, 2014, p.20). This notion of shooting led to artist’s desire for creating visual language to speak through their work where the image had the opportunity to write its own context. Photographers began experimenting with their medium and worked towards moving away from the association of the informative, evidential photograph as a means of historical reference. Aside from the partnering of art and text, it is essential to discuss the expansion of the lone image and its uncoded connotations. In contrast to the use of language in conceptual art, where it is shown with intent and purpose and the use of text being either caption or narrative, it is crucial to consider the unspoken language that is suspended in an image exhibited in the gallery space.Liz Kotz discusses Victor Burgin’s ideas adjacent to this where he articulates that:

Even the uncaptioned “art” photograph, framed and isolated on the gallery wall is invaded by language in the very moment it is looked at: in memory, in association, snatches of words and images continually intermingle and exchange one for the other.

(Burgin, 1986, p.69).

When observing an image, language is immediately evoked in the viewer’s consciousness even if writing is not existent in the work. The visual prompts aid the viewer into concentrating inside of the image as a way of seeing rather than a recording of information. The photographer seeks to experiment with elements that writing cannot apply, this is displayed through different methods and styles distinct to them.

An artist that is an exemplar of this notion of experimental photography is Swiss artist Walter Pfeiffer.Considering artist’s methods being individual to them, Pfeiffer states in an interview with Sarah Moroz that “When I have to think a lot before I do the picture, the picture maybe is gone. I have to be quick, and I have to find away — my way.” (Pfeiffer, 2016, np). With an uncluttered attitude, Pfeiffer’s process is simplistic yet consistently successful. This is due to a vision of seeing more than the fundamentals of a photograph. His visual language evokes emotion and excitement due to his influence of youth culture, eroticism and fashion. With a laid-back strategy, his photographs are charismatic and his artistic flair is prominent throughout his career. By shooting on a standard 35mm camera, picking a model and using a collection of garish props, he then allows the rest of the shoot to be open to any chance happening that may occur. Where he has a distinct routine that is rarely changed, there is stillroom for chance happenings. This can be linked to the idea of ‘the anticipatory with the reactive’ whereby the photographer can anticipate the outcome of an image by preparing for the moment. Pfeiffer fulfils this with a regular routine then reacts his surroundings that is patent throughout the shoot. This, therefore, creates a sincere narrative for each image and ultimately, evokes an arresting visual language that the audience can effectively respond to.

Certain compositions move for interpretation and visual language opens possibilities for both the artist and the viewer. Allan Sekula discusses the photographic meaning as a firm language and its relation to discourse. “A discourse can be defined as an arena of information exchange, that is, as a system of relations between parties engaged in communicative activity” (Sekula, 1982, p.84) This term is compared with photography and how it can function as a communicating system as successful as written language. Pfeiffer’s relaxed shooting strategy results in relaxed yet loud images, they communicate with the viewer through the artist’s creative limitations.

In Clive Scott’s The Spoken Image, the individual traits of an artist are addressed as Scott states that “self-expression can infiltrate the photographic process where choice is involved” (Scott, 1999, p.21). Photographic language is now depending solely on the power of the artist and how they respond to their own environment. The photograph’s outcome is their own impressions of the world and how they seek meaning from it. In contrast, it is critical to recognise that while the artist portrays the language they wish to envelop, the viewer’s conscious and subconscious thoughts are still acknowledged as the absence of text allows conscious word associations. How the viewer responds to the image is exclusively their own prerogative where they can process the visual elements that constitute an unwritten language. To break the mental process of the viewer down, there must be an understanding of the resemblance and likeness an image may represent. This image may represent an individual memory, fantasy, idea that the viewer is aware of but this makes each visual experience singular. Looking again at The Spoken Image, Scott discusses the two viewpoints in how both the artist, who grasps the world, and the viewer who responds to the artist’s work. He states:

First, from the point of view of the photographer who selects and interprets a scene.Second, from the perspective of the viewer who interprets (reads) the photograph in the process of decoding

(Scott, 1999, p.23)

The use of the word decoding is significant as the viewer processing the photograph must investigate the components forming the image to then be able to decode the image that, effectively, has no code.To de-construct the image’s language, the viewer must break down what the artist has intentionally set up. The visual language in which we are reacting to is dependent on the technicalities of the photograph. The light the artist uses, the shadows and the visual prompts for instance, colour, subject or location. In Nelson Goodman’s chapter in Iconology Image, Text,Ideology he expresses that “every modification of texture or colour is loaded with semantic potential” (Goodman, 1986, p.67) The constructs a photographer follows to create a photograph is essential in communicating the language to the viewer. It is the only opportunity whereby they can control how the audience may respond to their work and furthermore, in its success of communicating the context they intended.

To conclude, it is principal to identify the theme of a strategy within each movement raised in this essay. From the decided upon constraints the Conceptual artists imposed on themselves to the methods of the 1970s experimental photographers. Where language is concerned, a certain strategy is fulfilled.The strategies have influenced each movement and there have been pinnacle moments in both the artist’s possibility and their chosen medium, language.

Using the examination of both art and music, we have looked at how the experimental compositions of the 1950s inspired parts of Conceptual art which has aided proof that language is key in assisting an audience to understand something further than the visual. The combination of art and text was a fundamental step in art towards a new occurrence of contemporary work where there were direct links between the artist and the viewer. Considering text as juxtaposition, we can recognize language as form and how it can be used to confuse and deceive the viewer through works by artists such as William Anastasi. Thus, tension is raised between the artist and viewer and communication is questioned of its authenticity.

The language works of Mel Bochner and his close relationship with the medium can be compared to that of Walter Pfeiffer whereby they both follow steps to create their work. Bochner’s methods, however, are more restrictive than Pfeiffer’s more relaxed approach. With Bochner exploring elements such as texture and space, Pfeiffer seeks to create a visual language through lighting, colour and subject. To depict language in art and photography, these fundamentals must be considered and utilized correctly. Both Mel Bochner and Walter Pfeiffer continued to make art and images in a similar nature which proves that the opportunities that language brought to art continued to develop and enthuse artists throughout their respective careers. The themes of language are still relevant in contemporary work and continue to be pushed by both founding figures of its development and new contemporary artists.

We have addressed the importance of the relationship between image and text and how this shaped photography after conceptual art. The pairing is useful and considered “the “body” and “soul” of the emblem” (Gilman, 1980, p.61) as it serves context where both lack to do so alone. The importance of both the written word and the image is key in Keith Arnatt’s Trouser- Word Piece where he invites the audience to look at the work theoretically, an avenue that wasn’t frequently visited. In comparison, we have also investigated the power of the image alone and the emotions it can evoke. The benefits of the image alone are important in the context of the viewer as they can invite individual connotations using visual prompts. The viewer then becomes singular and the communication between artist and viewer is more personal and inviting. Where photography is concerned, the idea to “transcend the ordinary” (Cole, 2014, p.6) is crucial in reaching out to its viewer in conveying a unique recognition of the world. The image also allows the artist to speak directly to the viewer using only visual elements.

As artistic technology develops and language evolves with generation, the conclusion is not definite. Where we can see strategy patterns within both conceptual art and new experimental photography, there is a continuation for new challenges of breaking away from the conventional photograph and artistic paradigms. We, as a viewer, can consider art and photography through language and memory to allow ourselves into its context and respond to it. We look to see where we are in the image and we are guided by the artists and their personal visions.

Questions are raised as to whether more can be produced with text over the photograph alone. Where there is one image, there are multiple word associations to be written. However, there are multiple interpretations with the image alone as the viewer is invited to understand subjectively in their own language and context with the artist’s direction. The mind of multiple viewers could be stronger than that of the artist’s alone. In contrast, we also consider that“the artist always has final say” (Norris Webb, 2014, p.104) and question whether the artist's mind is further advanced than the combined audience and we seek to find overall, who asserts dominating power.

The written language, if used, must be executed well enough to provoke thought or create humour and mystery for the sake of the viewer. Whereas, the photograph must be constructed well enough to lead the audience to new paths of narratives and connotations. Language continues to boast innovative directions in art and should be recognized as a succinct method for artists to both communicate with their contemporary audience and as context to their own concept.

Bibliography

Alberro, A. (1996). MEL BOCHNER: THOUGHT MADE VISIBLE1966-1973. Artforum International, p.80+.

Artequalstext.aboutdrawing.org.(2018). Robert Brennan on William Anastasi | Art=Text=Art. [online]Available at: http://artequalstext.aboutdrawing.org/william-anastasi/

Barber, C.(1964). The Story of Language. Pan Australia.

Bateman, J.(2014). Text and Image. New York: Routledge.

Blacksell, R. (2013). From Looking to Reading: Text-BasedConceptual Art and Typographic Discourse. Design Issues, 29(2),pp.60-81.

Burgin, V. (1982). Thinking photography. Basingstoke:Palgrave Macmillan.

Costello, D. and Iversen, M. (2014). Photography afterconceptual art. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Foucault, M. (1982). This Is Not a Pipe. Berkeley andLos Angeles, California: University of California Press.

Galeriesultana.com.(2018). Galerie Sultana - Walter Pfeiffer. [online] Available at:http://www.galeriesultana.com/shows/walter-pfeiffer

Herbert, M. (2008). Keith Arnatt: I'm a Real Photographer. ArtMonthly, 314.

Knight, N. (2007). Slowly Adapting Art: Moving with the TimesRe-installing Originals. The Oberlin Review.

Kotz,L. (2007). Words to be looked at. MIT Press

Kotzee, B.(2018). Language Learning in Wittgenstein and Davidson.

Lomax, Y.(2000). Writing the image. London [etc]: I.B. Tauris.

Mitchell,W. (2005). The language of images. Chicago: The University ofChicago Press.

Mitchell,W. (2009). Iconology. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press.

Moroz, S. (2019). walter pfeiffer photographs the eternal,erotic power of youth. [online] I-d. Available at:https://i-d.vice.com/en_us/article/xwxnqz/walter-pfeiffer-photographs-the-eternal-erotic-power-of-youth[Accessed 2019].

O' Neill, A. (2019). The Cult of Walter Pfeiffer.[online] Aperture Foundation NY. Available at:https://aperture.org/blog/cult-walter-pfeiffer/.

Osborne, P. (2002). Conceptual art. London: Phaidon.

Petty, F. (2019). walter pfeiffer: spirit, freedom andbeauty. [online] I-d. Available at:https://i-d.vice.com/en_uk/article/evxgv7/walter-pfeiffer-spirit-freedom-and-beauty[Accessed 2019].

Philosophyfor change. (2018). Meaning is use: Wittgenstein on the limits oflanguage. [online] Available at:https://philosophyforchange.wordpress.com/2014/03/11/meaning-is-use-wittgenstein-on-the-limits-of-language/

PHOTOGRAPHY 1979, Photographyand language: exhibition catalogue, Nfs Press.

Photoworks.(2018). Keith Arnatt, 1930-2008 - David Bate | Photoworks. [online]Available at: https://photoworks.org.uk/keith-arnatt-1930-2008/ [Accessed2018].

Sayers, G.M. (2002) "Ofpipes, persons, and patients", Medical humanities, vol.28, no. 2, pp. 88.

Schlatter, N.(2018). Art=Text=Art: Works by Contemporary Artists. [online] URScholarship Repository. Available at:https://scholarship.richmond.edu/exhibition-catalogs/2/

Scott, C. (1999). The spoken image.Reaktion Books Limited

Selby,A. (2009). Art and text. London: Black Dog.

WalterPfeiffer. Artist Talk: Taking the Challenge: The Art of Walter Pfeiffer. (2012). [DVD] EuropeanGraduate School Video Lectures.

Webb, A., Webb, R. and Cole, T. (2014). Alex Webb andRebecca Norris Webb on street photography and the poetic image. New York:Aperture.

Wittgenstein,L., Hacker, P. and Schulte, J. (n.d.). Philosophical Investigations.